-

Black tea is black tea (as opposed to purple tea) because of oxidation. If you cut an apple (or banana or zucchini etc.) in half and let it sit, within a few minutes the exposed flesh start to turn brown. That’s oxidation.

Turning brown: which is perfectly safe, it’s just oxidation

And that is what happens to make black tea. They roll, crush, tear, cut, and/or curl the tea leaves; this is the equivalent of cutting the apple. Thus they expose the interior of the plant, disrupting the cell membranes to air.

A rolling machine in Sri Lanka, crushing the leaves, making them juicy—the precursor to oxidation.

The tea leaves get all juicy, just like an apple gets juicy if you cut it. If they are making black tea, they spread the juicy leaves out on a long flat surface, like a trough, table, or even the floor (using a tarp), and let the leaves turn brown. That's oxidation. If they leave the leaves out long enough, they oxidize fully and become black tea. It is relatively easy to stop or prevent oxidation. Apply gentle heat to the leaves, which kills the enzymes in the leaf and prevents oxidation from occurring, or stops the oxidation at that point. No browning.

Why do tea folks bother with oxidation? Without it, all you would have is white or green teas. I love white and green teas, but if someone took my Grand Keemun away I would go crazy. The date and origin of deliberate oxidation as a process for making black tea is not certain. Fujian has been making what would now be considered black tea since the late Ming dynasty, but large scale production did not take place in China until the 19th century. It is important to understand that for all intent and purposes black tea is NOT drunk in China—at all. They make a remarkable amount and variety of black teas in China, but they don’t drink them. It’s not completely crazy to speculate that oxidation was “invented” by mistake.

What happens during oxidation? The plant gives off H2O (water evaporating) and absorbs extra oxygen from the atmosphere which, with the enzymes in the leaf, triggers a whole bunch of chemical reactions, causing the leaf to turn black/brown, the flavor and aroma to change, etc. etc.

Tea Geek facts about tea oxidation:

- If you really want to be annoyingly literal about it, ALL tea goes through some degree of oxidation, albeit, sometimes a VERY minor degree of oxidation. Because oxidation begins the moment the leaf is plucked from the tea plant.

- -White and green tea both go through probably less than 5% oxidation- basically just what happens during transport and handling-- in fact they are trying to prevent and arrest oxidation. Oolongs can be oxidized through a large range, anywhere from 12- 90%.

- Black teas typically go through close to 95-100% oxidation

- Teas going through oxidation smell AMAZING: intoxicating, addictive, intense, sweet, fruity, alive….

- When black teas are going through oxidation, the leaves are spread out on a surface, maybe a table--that's called the "dhool" table.

- Oxidation is fast, for whole leaf teas it can be up to four hours or so. For a small particled tea (CTC), as little as 90 minutes.

A dhool table (or trough) in Ceylon, the tea would be spread out across these areas.

And yes, there is a purple tea. In fact, there are two kinds of purple tea, both are real tea from the camellia sinensis plant- one from Africa and one from China. Watch this blog for more info.

-Bill

-

To confess, when I was growing up, all "tea" was "black tea" to me. Boring. And as far as I knew, it grew in tea bags that hung from Lipton trees. When green tea had its renaissance in the 90’s as some form of exotic “cure-all”, I began to take interest (and enjoy it thoroughly). But when I learned black and green tea come from the same mysterious source (a plant otherwise known as camellia sinensis), I realized I had been fooled.

The defining feature of black tea, allowing the leaves to fully oxidize, is not as simple as it sounds. There are innumerable factors that go into the process, beginning with geographic location. Local terroir and the particular tea cultivar planted in that region will have a huge impact on the outcome of that tea before the leaves have even been plucked. Local traditions and history may be the biggest factor. China, where black tea originated, has its own unique regional styles. But if the tea growing region was initiated by the former British Empire (India, Sri Lanka, Africa), this will have its own particular impact on the methods used. In Taiwan, their modern black teas are often being produced by the same farmers who have been making oolong tea for decades.

Local traditions and history may be the biggest factor. China, where black tea originated, has its own unique regional styles. But if the tea growing region was initiated by the former British Empire (India, Sri Lanka, Africa), this will have its own particular impact on the methods used. In Taiwan, their modern black teas are often being produced by the same farmers who have been making oolong tea for decades. Even when the regions are inside the same political border, the outcomes can be wildly different. The Darjeeling and Assam regions of India are not geographically far apart, but produce teas that are nothing alike. Part of this is because Darjeeling uses the small-leaf Chinese tea plant, camellia sinensis-sinensis, smuggled out of China by the British spy Robert Fortune. This sub-species prefers high elevations and cooler temperatures. Assam uses their own indigenous plant, camellia sinensis-assamica, whose large leafs produce thick, lush teas and prefer the tropical climate of the Assam valley.

Even when the regions are inside the same political border, the outcomes can be wildly different. The Darjeeling and Assam regions of India are not geographically far apart, but produce teas that are nothing alike. Part of this is because Darjeeling uses the small-leaf Chinese tea plant, camellia sinensis-sinensis, smuggled out of China by the British spy Robert Fortune. This sub-species prefers high elevations and cooler temperatures. Assam uses their own indigenous plant, camellia sinensis-assamica, whose large leafs produce thick, lush teas and prefer the tropical climate of the Assam valley.

My original (and ignorant) assumption was that black tea was somehow boring and homogenous. I couldn’t have been more wrong. The variety is staggering. A well made first flush Darjeeling tea from India and a first grade Keemun from China are so different that it’s hard to recognize both of them as black teas. But that is why it is so fascinating.

-Michael Lannier

TeaSource manager -

I love it when an experience totally takes me by surprise; especially over the course of a wonderfully fun night.TeaSource manager Jess Hanley and I recently spent an evening planning, tasting, and schmoozing with one of the Twin Cities best known cheese geeks, Steven Levine. This was in anticipation of an upcoming workshop, Tea & Cheese: A Perfect (and Unexpected) Pairing, at our Eden Prairie store on Saturday, October 26th. We figured we better get together and play with some cheeses and tea for a while so we had an idea of what we would do on Saturday. Steven brought along eight different cheeses that we were going to try match with teas then narrow them down to five or six cheeses for the workshop. We started working our way through the cheeses, basically taking a lightest to heaviest approach. We went in thinking we would just try to pair cheeses and appropriate teas: choosing teas that complimented, contrasted, or provided a base or background note for the cheese. It didn't work out that way. It started with the first cheese: a very fresh, lovely, mild, local, goat cheese. It quickly became apparent that it wasn’t just a question of whether this tea tastes good with that cheese. The teas were actually changing the taste profiles and flavor notes of the individual cheeses. And the reverse was happening. We nibble a cheese, take a swallow, taste the cheese a 2nd time and all of a sudden there were all these notes from the cheese that weren't there on the first nibble. It was NOT subtle changes; it was like a whole different range of notes.

It would happen in the other direction too; try the tea first, then the cheese, then the tea again. And the tea would literally taste phenomenally different than the first sip: sometimes it would become muted, sometimes, individual notes would shine at the expense of others, and sometimes there would just be tastes that weren't there the first time. This happened with all eight cheeses (and teas), to varying degrees-sometimes dramatically so. All three of us were knocked over by this phenomenon. There may be gastronomes (old speak for foodies) out there to whom this is a common experience. But I wasn’t ready for it. Again I stress, it wasn't simply a case of two things tasting good together. It was the combination of these two foods within your mouth, changing the way the palate experiences the flavors available to it. It was wild. My favorite pairing was a five-year-old Gouda with a crumbly almost cheddar-like texture, matched with our Jin Jun Mei (an incredibly rich, sweet, velvety, black tea from Fujian). The taste sensation even changed depending on which direction we went: tea first then cheese, then tea again. Or vice versa, letting the cheese lead. We ended up not being able to eliminate any of the eight cheeses, they were all so good. So, on Saturday, October 26 we will be cupping up eight world-class cheeses with eight world-class teas--- and turning people’s palates upside down. There are still a few slots left open, but I expect the class to fill up fast. If you're not in the Twin Cities try this at home: seriously it’s amazing. After the class I will post the actual pairings we worked up. You'll experience tastes you've never tasted before, and that's a pretty rare experience. -Bill

It would happen in the other direction too; try the tea first, then the cheese, then the tea again. And the tea would literally taste phenomenally different than the first sip: sometimes it would become muted, sometimes, individual notes would shine at the expense of others, and sometimes there would just be tastes that weren't there the first time. This happened with all eight cheeses (and teas), to varying degrees-sometimes dramatically so. All three of us were knocked over by this phenomenon. There may be gastronomes (old speak for foodies) out there to whom this is a common experience. But I wasn’t ready for it. Again I stress, it wasn't simply a case of two things tasting good together. It was the combination of these two foods within your mouth, changing the way the palate experiences the flavors available to it. It was wild. My favorite pairing was a five-year-old Gouda with a crumbly almost cheddar-like texture, matched with our Jin Jun Mei (an incredibly rich, sweet, velvety, black tea from Fujian). The taste sensation even changed depending on which direction we went: tea first then cheese, then tea again. Or vice versa, letting the cheese lead. We ended up not being able to eliminate any of the eight cheeses, they were all so good. So, on Saturday, October 26 we will be cupping up eight world-class cheeses with eight world-class teas--- and turning people’s palates upside down. There are still a few slots left open, but I expect the class to fill up fast. If you're not in the Twin Cities try this at home: seriously it’s amazing. After the class I will post the actual pairings we worked up. You'll experience tastes you've never tasted before, and that's a pretty rare experience. -Bill

View Post About The Big Cheese: Tasting Things You’ve Never Tasted Before

-

Why Taiwan tea? If you had to ask the question, you haven’t tried them. Taiwan has tens of thousands of small tea growers, many of them family operations, and the industry is almost synonymous with oolong.

Michael rolling tea incorrectlyMaking Taiwanese oolongs is a long process and requires a lot of experience to get it right. After witnessing how oolong is made on a trip to Taiwan in 2011, I realized I am a very lazy and impatient person. I also realized I’m really bad at tea producing skills such as “rolling” and “withering” (which involves staring at the leaves for about 14 hours – it takes forever). Though few of my instructors spoke English, they knew how to yell “No” just like my father, and show me again how to do it right. To know when the leaves are done withering, they simply pick them up and smell them – and I couldn’t tell the difference at 6 hours, 10 hours, or 14 hours – which is when they said it was ready.

Michael withering tea incorrectlyBut I did learn a couple things while I was there. The first thing I learned was an immense respect for the wisdom and discipline to master what is essentially an art form. I also learned that when I was not ruining their tea leaves, the Taiwanese are otherwise very nice and welcoming people. I was amazed at their patience with my lack of Chinese speaking skills and their inclusiveness of total strangers. I also learned a little bit about the basic styles of Taiwanese teas, and what to look for.

Here are a couple of my notes:

Pouchong or Bao Zhong (translation: scented variety) – loosely defined as a lightly oxidized oolong with long, twisted, emerald green leaves, typically from Wenshan in northern Taiwan. The Chin Shin cultivar is commonly used to highlight the very fragrant nature of this tea. Look for a spectrum of sweet, strong-floral tones on top and bright, but subtle vegetal flavors underneath. The complexities of pouchongs will fade quickly once exposed to air so buy vacuum sealed if possible and store airtight.

Tung Ting or Dong Ding (translation: frozen peaks) – Though Mount Tung Ting is covered with tea plants, modern usage of “Tung Ting” often refers to a style of tea grown in Nantou county by which the leaves are rolled and compressed into “semi-ball” or “bead” style rather than the long twisted leaves of pouchong. These teas are often distinguished by what mountain they were grown on, which cultivar was used, and what degree of baking they went through (note that not all teas of this style will be referred to as Tung Ting – yes, it’s confusing to me too).

Tung Ting styles that are lightly oxidized are often referred to as “Jade Oolongs” for the bright green color. Other times the tea may be “baked” at the end of the process to deepen the character. The flavor profiles of these teas will vary widely depending on any of the above mentioned factors, ranging from soft and floral to deep and toasty.

Oriental Beauty, also know as Bai Hao Oolong or Silvertip Oolong, is one of Taiwan’s most famous (and expensive) teas. The tea is made only in mid-summer when the “Green Leaf Hopper” arrives to feed on the new growth tea leaves, which are then immediately harvested. This “feeding” causes a chemical reaction in the plant meant to drive the insect away, but it is also responsible for the sweet honey notes of a great Oriental Beauty.

When buying an Oriental Beauty I look for teas with sparkling, floral, apricot notes on top; and honey-woodsy-spicy notes in the bass. The leaves should have a stunning contrast of bright silver tips over twisted bronze leaves. It is called Oriental Beauty for good reason.

I could go on forever (I already have). This only scratches the surface. All I’ve learned so far is that I have a lot to learn, and besides the tea itself, that’s the best part.

-Michael Lannier

TeaSource Manager -

Spring is a special time for many cultures. In America we write songs about spring: -Spring Will Be a Little Late This Year -Springtime for Hitler and Germany -Spring Fever -It Might as Well Be Spring In the tea world they make special teas in spring… or do they? [caption id="attachment_216" align="aligncenter" width="604"]The tea bushes from which our 2013 Tai Ping Hou Kui was made. Photo taken April, 2013, Huang Shan Mountain region, Anhui Province, China[/caption] You always hear ‘spring picked teas are the best.’ Like most generalities there is some truth to this, but there are also a lot of exceptions. Why the heck would spring teas be the best anyway? I have spoken to tea botanists about this and their answer makes perfect sense: in most tea growing regions tea plants are dormant during the winter. This means that during those quiet months the plants are recovering from the previous year’s harvest. During that dormant period, and into the very early spring the plants are replenishing those chemicals which in the tea leaves produce those amazing aromas, tactile sensations, and flavors. The leaves will literally have greater amounts of sugars (glucose et al), and various flavor compounds (eg. theaflavins) for that first plucking. If you are a gardener, it is very similar to the fact that the first of the sweet peas or corn or the zucchini or whatever tends to be sweeter, more tender, has increased taste—it’s often bursting with flavor. The same with tea. Spring teas, especially green and white teas can be amazing and truly special. [caption id="attachment_217" align="alignright" width="357"]

Tea fields undergoing drought conditions[/caption] But this only happens if a particular region is having an overall good year for tea. If they are having a drought, too much rain, too cold or too hot the spring teas may not be so great—in fact they can be inferior to the same tea made later in the year. Like always, it comes down to the individual tea. But, make no mistake a great spring tea can make your eyes roll back in your head and your toes curl. [caption id="attachment_218" align="alignleft" width="220"]

Tea fields undergoing drought conditions[/caption] But this only happens if a particular region is having an overall good year for tea. If they are having a drought, too much rain, too cold or too hot the spring teas may not be so great—in fact they can be inferior to the same tea made later in the year. Like always, it comes down to the individual tea. But, make no mistake a great spring tea can make your eyes roll back in your head and your toes curl. [caption id="attachment_218" align="alignleft" width="220"] Fresh plucked, plumb, leaves that will be made into Huang Shan Mao Feng[/caption] When I am considering buying/importing a spring tea from a grower, I always check the spring weather conditions for that region. I very closely examine the dry leaf; I look for tremendous color (specifics can vary depending on the type of tea). I often look for plumpness/thickness in the leaf- I am kind of looking for a Marilyn Monroe type of leaf, not a Kate Moss type. But these are just clues- ultimately everything depends on the steeped cup. Some of the names you will see associated with spring teas are: -88th Night Shincha- a Japanese first flush green tea, plucked on the 88th day of spring -Before the Rain Teas; picking of these Chinese teas begins in late March just before the Qing Ming Festival (around April 5th) and up to around April 20th. -Green Snail Spring: aka Pi Lo Chun, this Chinese green tea may be made throughout the tea season, but traditionally the very best is made in early spring. [caption id="attachment_219" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

Fresh plucked, plumb, leaves that will be made into Huang Shan Mao Feng[/caption] When I am considering buying/importing a spring tea from a grower, I always check the spring weather conditions for that region. I very closely examine the dry leaf; I look for tremendous color (specifics can vary depending on the type of tea). I often look for plumpness/thickness in the leaf- I am kind of looking for a Marilyn Monroe type of leaf, not a Kate Moss type. But these are just clues- ultimately everything depends on the steeped cup. Some of the names you will see associated with spring teas are: -88th Night Shincha- a Japanese first flush green tea, plucked on the 88th day of spring -Before the Rain Teas; picking of these Chinese teas begins in late March just before the Qing Ming Festival (around April 5th) and up to around April 20th. -Green Snail Spring: aka Pi Lo Chun, this Chinese green tea may be made throughout the tea season, but traditionally the very best is made in early spring. [caption id="attachment_219" align="aligncenter" width="604"] TeaSource 88th Night Shincha, 2013[/caption] For most Japanese and Chinese white, green, and oolong teas it is assumed that the spring teas of any particular type of tea will be superior, more aromatic, sweeter, and more flavorful (and more expensive) than a tea from later in the season. And this is often the case. But, you have to taste the tea, you can’t assume a “Spring tea” is going to be better. That is a major part of our job at TeaSource, tasting and evaluating - making sure any “Spring tea” we carry, is worthy of the name. What about black teas? Well, the term often used to describe spring black teas is “first flush” which literally means the first picking of leaves. And this term is most commonly used with Darjeeling teas. Great Darjeeling first flush teas can be amazing. They are usually made in March/April. They can be light, very bright, astringent, somewhat fruity, aromatic, and enlivening. In an interesting marketing twist, black tea growers are starting to use the “flush” terminology to market other black teas, besides Darjeeling. I’ve started to see first and second flush Assams, and even China “first flush” black tea. First flush black teas, while very aromatic and tasty, usually do not have the body or weight of the same tea plucked later in the year. For instance, first flush Assams often are very bright, even crisp, but they tend to be thinner (they don’t have as many bass notes), but second flush Assams are those more traditional Assams with heavy, thick colory, liquors, though they may lack the delicacy and complexity of a spring black tea. It can be a trade-off. But, there are some black teas, particularly from China, that are in their glory as spring harvest teas. For instance, Jin Jun Mei, one of our new spring teas. This black tea is harvested around the Qing Ming Festival and has a truly amazing flavor. [caption id="attachment_220" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

TeaSource 88th Night Shincha, 2013[/caption] For most Japanese and Chinese white, green, and oolong teas it is assumed that the spring teas of any particular type of tea will be superior, more aromatic, sweeter, and more flavorful (and more expensive) than a tea from later in the season. And this is often the case. But, you have to taste the tea, you can’t assume a “Spring tea” is going to be better. That is a major part of our job at TeaSource, tasting and evaluating - making sure any “Spring tea” we carry, is worthy of the name. What about black teas? Well, the term often used to describe spring black teas is “first flush” which literally means the first picking of leaves. And this term is most commonly used with Darjeeling teas. Great Darjeeling first flush teas can be amazing. They are usually made in March/April. They can be light, very bright, astringent, somewhat fruity, aromatic, and enlivening. In an interesting marketing twist, black tea growers are starting to use the “flush” terminology to market other black teas, besides Darjeeling. I’ve started to see first and second flush Assams, and even China “first flush” black tea. First flush black teas, while very aromatic and tasty, usually do not have the body or weight of the same tea plucked later in the year. For instance, first flush Assams often are very bright, even crisp, but they tend to be thinner (they don’t have as many bass notes), but second flush Assams are those more traditional Assams with heavy, thick colory, liquors, though they may lack the delicacy and complexity of a spring black tea. It can be a trade-off. But, there are some black teas, particularly from China, that are in their glory as spring harvest teas. For instance, Jin Jun Mei, one of our new spring teas. This black tea is harvested around the Qing Ming Festival and has a truly amazing flavor. [caption id="attachment_220" align="aligncenter" width="604"] The bushes from which our Jin Jun Mei was made, photo taken March, 2013, Wuyi County, Fujian Province, China[/caption] [caption id="attachment_222" align="aligncenter" width="604"]

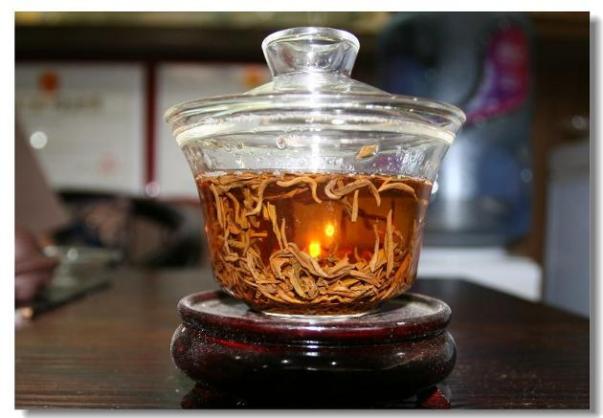

The bushes from which our Jin Jun Mei was made, photo taken March, 2013, Wuyi County, Fujian Province, China[/caption] [caption id="attachment_222" align="aligncenter" width="604"] The golden leaves and golden liquor of Jin Jun Mei in a Chinese traditional gaiwan.[/caption] If spring teas are so great, why is TeaSource featuring them in the fall? Even though it is the 21st century, it still can take 1-4 months to get teas from origin to Minnesota. Some spring teas we air-ship and get them within a few weeks of harvest, and we make them available immediately. Other spring teas, for various reasons, we have to ship by sea and this can easily take 2-4 months. Chinese teas have been particularly challenging the last few years, as the Chinese government has tremendously increased the inspections on any export food item, like tea. This means Chinese teas are some of the safest in the world, but it really increases the amount of time it takes to get them to Minnesota. So, all September, we are featuring most of our 2013 spring teas. Remember we’ve already weeded out the ones that weren’t Marilyn Monroe-ish. All that is left are those spring teas that stop you in your tracks, take your breath away, and leave you struggling to find words. Enjoy.

The golden leaves and golden liquor of Jin Jun Mei in a Chinese traditional gaiwan.[/caption] If spring teas are so great, why is TeaSource featuring them in the fall? Even though it is the 21st century, it still can take 1-4 months to get teas from origin to Minnesota. Some spring teas we air-ship and get them within a few weeks of harvest, and we make them available immediately. Other spring teas, for various reasons, we have to ship by sea and this can easily take 2-4 months. Chinese teas have been particularly challenging the last few years, as the Chinese government has tremendously increased the inspections on any export food item, like tea. This means Chinese teas are some of the safest in the world, but it really increases the amount of time it takes to get them to Minnesota. So, all September, we are featuring most of our 2013 spring teas. Remember we’ve already weeded out the ones that weren’t Marilyn Monroe-ish. All that is left are those spring teas that stop you in your tracks, take your breath away, and leave you struggling to find words. Enjoy.

-

Who would think tea professionals would ever get into disagreements that escalate into shouting matches? Certainly not I. But I’ve seen that when tea industry folks talk about white tea. I’ve even seen this at trade fairs and tea discussion panels at conventions. Thank goodness no punches were thrown—although with tea geeks like me, it probably would have been limited to ineffectual slaps? For the whole month of August TeaSource will be shining a spotlight on white teas, so this seemed the perfect time to talk about a fundamental tea difference of opinion.

Bai Hao Silver Needles Buds waiting to be pluckedFreshly plucked leaf for white tea

The first question is: what is white tea? In terms of production: white tea goes through the simplest of production processes. It begins with a unique gentle solar withering step, which can extend many hours, even into days, where they are using sunlight to help wither the leaves. Second, very limited oxidation occurs with white tea. This step is typically eliminated in the production process. But a minimal amount of oxidation occurs naturally over the course of manufacture. And thirdly, white teas typically, have no physical manipulation of the leave itself during manufacture: no rolling, twisting, panning, shaking, jiggling, caressing, tickling, etc. So stated very simplistically the production process of white is: a very long sun-wither, followed by drying. In terms of history: white tea traditionally is made in and around three small locales in Fujian province of China, the counties of Fuding, Jianyang, and Zhenghe. And naturally it would only be made from tea plants native to those locales. Some people say only tea made from those locales and those plants can be called white tea.

White tea fields in Fuding, Fujian, ChinaAnd this is where the fight begins. Is white tea defined by production process? Or is it defined by geography? This is very similar to the argument over Champagne. Does it have to be from the Champagne region of France? Or is a sparkling wine, made with the same production process the same grapes, and tasting roughly the same, but made in regions outside of France, still Champagne? I tend to not to take these kind of arguments too seriously, but to be fair this is a very legitimate question; especially for those small tea farmers in Fujian who have been making white tea for generations. All of a sudden white tea has grabbed worldwide attention and consumer interest. After more than a century of hand-making a wonderful little tea, mostly for their own local consumption, finally there is a larger demand for their product. This is their chance to get ahead. Is it right for folks who have only been making white tea for the last 5-10 years, to cash in on this sudden interest in white tea? But on the other hand these newbie white tea producers are typically using the exact same Fujian production processes, often using the Fujian tea plant cultivars, and not infrequently bringing in Fujian tea growers and manufacturers themselves to new regions to make these teas. In many cases this new white tea production has added a much needed spark to local tea industries outside of Fujian. And their white teas may look and taste as close to a Fuding white tea, as Fuding white tea tastes compared to a Zhenghe white tea. As I said, we are now in the realm of tea geeks.

TeaSource Bai Hao Silver Needles, from Fuding, Fujian, China on left, and Silver Peony White tea, from Yunan Province on right

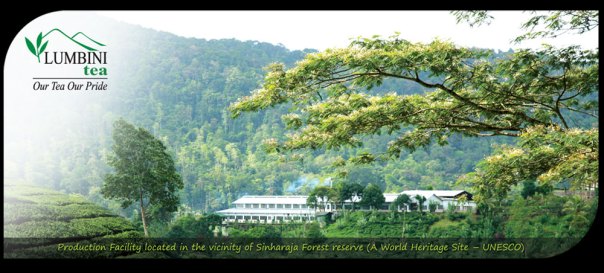

But nonetheless this is an important question, and you should consider it as you buy white teas. You should know where you tea vendor stands on this issue, and exactly where their white teas are from. I believe the “process” defines white tea, not the geography. So TeaSource may carry white teas from many different regions. But we will always identify them when that is the case. In the past if we didn’t say otherwise we assumed people knew it was from the traditional regions of Fujian. In the future we will always try to be more specific, even about teas from the traditional areas. We hold this position (of white tea being defined by the process) because we believe the world of tea is constantly changing and evolving. And we think this is a very good thing. There are many teas that didn’t exist a few years ago. For example, Ruby 18 from Taiwan didn’t exist five years ago. White tea from Ceylon didn’t exist about 15 years ago. Shou puer didn’t exist 40 years ago. Tea from India didn’t exist 175 years ago. This kind of change and evolution is part of what makes the world of specialty tea exciting and vibrant. As with any change there are some who like it and some who are dismayed. We feel this kind of change is part of the natural processes in the world of tea. So who the heck else is making white tea? Many other China provinces, India, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Japan, Malawi… I had the privilege to purchase the very first white tea ever produced in Sri Lanka, almost 15 years ago. I was visiting the Lumbini Estate in southern Sri Lanka (one of our favorite estates and favorite tea growing families), when Chaminda, the son of the Lumbini founder and now manager of the garden, showed me something special he had been working on, a small batch of Bai Hao Silver Needles. Needless to say his dad was very skeptical of his son’s ‘far-out” tea-making efforts. The tea was FANTASTIC. I bought all of it on the spot, about 40 kgs. When I got back into Colombo, on the way to the airport I had to stop and buy two gigantic duffle bags (think hockey equipment bags) to stuff this tea into and bring onto the plane as additional luggage. This was pre-9/11 when you could get away with this kind of thing. Although getting through Customs in Mpls, took some explaining. Unfortunately this Bai Hao Silver Needles from the Lumbini Estate has become so popular in Japan that the price has gotten out of the range of TeaSource.

The Lumbini Tea Estate in Sri LankaBefore long I think this fight about what constitutes white tea will start to fade away. For better or worse I think this horse has left the barn. The good news is that then when everyone stops talking about the definition of white tea, we will focus more on the tea itself. For white tea is a unique gift to the world of tea. The dry leaf is stunning, a botanical work of art. And the steeped cup is soft, shimmering, sweet, creamy, and evokes calm, peace, and grace. All through August we will have white teas on sale and tons of info and sampling available. And expect some additional posts about white tea.

–Bill Waddington

TeaSource, Owner

TeaSource Bai Hao Silver Needles